On this page:

Support the University Libraries

“Everything here has a back story,” says Michael Basinski, curator of the UB Poetry Collection, before launching into a whirlwind tour—back stories and all—of one of the world’s leading collections of 20th- and 21st-century poetry in English. One minute he’s pointing out the coffee stains on a handwritten copy of Dylan Thomas’s “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night”; the next, sweeping his hand over a set of paintings purported to be of James Joyce’s relatives (and carried by the Joyce family throughout Europe), but quite possibly, says Basinski, “purchased by Joyce’s father at a used furniture store in an attempt to gentrify the family.”

The Poetry Collection, now in its 76th year, defies most people’s idea of poetry, and that is in part what makes it so endlessly fascinating. In addition to a world-class collection of first editions, and scores of archives and original manuscripts (including the world’s largest James Joyce archive), there are avant-garde zines, little literary magazines, manifestos from the early days of Punk, collections of visual and concrete poetry, an eccentric collection of “mail art” by the likes of an organic chemist from West Virginia named Ficus Strangulenis, letters, photographs, artwork, even a sketch of the poet Robert Duncan by Robert De Niro’s mother.

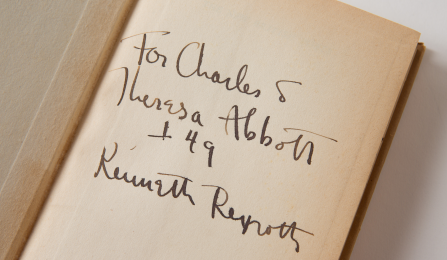

In other words, nothing is too far afield for Basinski, the collection’s eighth curator. In this, he follows in the footsteps of his seven predecessors and Charles Abbott, who founded the collection in 1937. Director of the university libraries from 1934 to 1960, Abbott was unlike most literary scholars at that time, in that he placed tremendous value on the work of living poets and cultivated a wide personal network. “Poets came to his home and he became friends with them,” says Basinski. “Then he harvested manuscripts from them and we now use them as calling cards.” Abbott also directed Mary Barnard, the collection’s first curator, “to write to poets and ask for, quite literally, the contents of their wastepaper baskets. At that point, contemporary poets were throwing their stuff away.”

Charles Abbott was married to Theresa Gratwick, whose family owned a 240-acre farm in Pavilion, N.Y., about 50 miles east of Buffalo. Theresa’s parents gave the caretaker’s house to Charles and Theresa, and this is where the couple entertained poets over the years, including everyone from William Carlos Williams to W.H. Auden. The third floor of the house served as Charles’ private office, and according to Basinski (who is now writing a book about Abbott), he was quite a collector of books in his own right.

So when Basinski learned from a friend that the house was slated for demolition, he made a visit to Pavilion to rescue what he could [see video at right]. “The dust was measurable, probably a quarter-inch, and the roof had rotted out,” he recalls. “Some rooms were already sealed. There were bats living in the house. It was quite decrepit.” Then he adds, with a characteristic glint, “But full of book treasure!”

Video: Rescuing Book Treasure from the Abbott Home

In Demand Around the World

The Poetry Collection frequently lends its literary treasures to museums worldwide. "We're not only a research library but a poetry museum," says curator Michael Basinski. Below is a partial listing of museums and galleries that have shown Poetry Collection holdings in recent years:

Britain's National Portrait Gallery

The Tate Britain

The National Library of Wales

The National Library of Ireland

The Guggenheim Museum in New York

The Guggenheim Museum in Venice

The Crocker Art Museum in California

24 ORE Cultura in Milan

Museum Ludwig in Köln, Germany

Poetry and Me

by Michael Basinski

Adapted from an article for UB Libraries Today

“It all began a long time ago when I oddly came upon ‘Love’s Philosophy’ by Percy Shelley: ‘The fountains mingle with the river.’ My imagination was christened and I committed to poetry. This was really not the easiest thing to do in working-class Cheektowaga. I read about Beatniks and Jack Kerouac in Mad Magazine. I ate plain yogurt and, whenever possible, drank espresso. There were few poets in the neighborhood and a lot of folks who knew how to change spark plugs. I persevered.

“At some point, I thought I should head off to college to study poetry. I worked the line at Buffalo China during the day and became a Millard Fillmore College student by night. The first class I walked into was Jack Clarke’s Modern Poetry. It was one of those ‘never look back’ moments. When I first appeared in the UB Poetry Collection as a disheveled graduate student looking for campus work, I was able to quote Charles Olson: ‘I have had to learn the simplest things last. Which made for difficulties.’

“I got the job. I never left. It’s a lifestyle! I still don’t know how to change a spark plug.”

Basinski received his PhD from UB in 1995 and was named the Poetry Collection’s eighth curator in 2004. In 2011, he received the SUNY Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Professional Service.

“There were few poets in the neighborhood and a lot of folks who knew how to change spark plugs.”

—Michael Basinski