Cravens World

If you’ve been to UB Anderson Gallery lately, you may have noticed that the Cravens Collection Room is closed. Although the door might be closed, the teaching collection is more alive than ever. With student help, we’ve been caring for the objects – photographing them, cataloging them, and creating a database that will be accessible online. We’re working on updates to the open storage room that will provide more context, research, and nuance to this collection, as well as to make it an even better tool for teaching and learning for students across every program at UB.

Cravens World displays a collection of archaeological, ethnographic, and art objects from all over the world, some of which date as far back as 4,500 BC. Donated to the UB College of Arts and Sciences in 2010 by Annette Cravens (1923-2017), MSW ’68, this collection of over 1,100 objects can be viewed and researched in a visible storage system at UB Anderson Gallery.

Director's Welcome

“During the planning of Cravens World and even after its public opening in 2010, I met regularly with Annette Cravens. Right up to her passing in 2017, we discussed how we can get people to visit Cravens World and how the collection can be used for not only UB student research, but to engage communities at various levels. Annette inspired us to think of this collection as a means to spark conversations and engage everyone from grade-school children to college students to the communities all around us.

In summer 2018, we invited local artists to visit the collection and draw a coloring book page for our young audiences. We released the Cravens Collection Coloring Book as an in-house, print-on-demand publication. We hope to expand on this existing work to encourage further conversations and interactions with this wonderful collection. During these extraordinary times dealing with the COVID-19 global pandemic, we are sharing some of the pages featured in the Cravens Coloring Book to extend our mission to provide access to art.”

-Robert Scalise, Director

SAMUEL NAHAULAITUQ (1923–1999, INUIT, CANADA), HUMAN FIGURE, 1984. SOAPSTONE, 6.25 X 4 X 11 INCHES.

Samuel Nahaulaituq was an artist who lived and worked in a territory now called Nunavut in northern Canada. Nahaulaituq worked in the Inuit carving tradition to depict humans and animals native to the region, some realistic and some more abstract. Although his primary material was soapstone, he also carved animal bone-like caribou and walrus ivory—materials that were more readily available in northern Canada. Nahaulaituq witnessed many changes to his culture and society during his lifetime, including the Canadian government’s forcible relocation of Inuit communities to permanent villages and cities in the 1950s. Although this permanent settlement drastically disrupted the Inuit ways of life, including seasonal migration and subsistence hunting, Nahaulaituq’s sculptures continued to depict subject matter that was important to the artist’s surroundings and culture.

Look for his sculpture in the virtual tour of Cravens World. In the same case, you can see a bear sculpture and two human figures on either side. These sculptures are also carved by Nahaulaituq. Check out more of his sculptures at the Canadian Museum of History.

“Soapstone is a soft, easy-to-engrave material that can be found in the Arctic. Other materials that are often used for carving and engraving in the region are granite, walrus ivory, and animal bones. While many older Inuit carvings are generally small and can fit in one’s palm, most soapstone figures in the Cravens Collection represent a turn to larger figurative forms in the second half of the 20th century.”

– Ya-Hsin Ko, Graduate, Media Study/Critical Museum Studies

What would you ask the artist, SAMUEL NAHAULAITUQ?

-Is it hard to carve a stone?

-How did you learn to carve?

LUCY LEWIS (1890-1992, ACOMA PUEBLO, NEW MEXICO, USA), POTS, 1988 (LEFT); UNDATED (RIGHT). EARTHENWARE WITH PIGMENT, 3.5 X 3.5 X 4.5 INCHES (LEFT); 4.5 X 4.5 X 3.875 INCHES (RIGHT).

Lucy Lewis is one artist whose earthenware storage vessels or pots can be seen in the Cravens Collection. Lewis was from Acoma Pueblo or the “Sky City,” a village located atop a five hundred-foot tall mesa in northwestern New Mexico. Growing up, Lewis learned how to make pottery from her great aunt. This included gathering and mixing natural clay, shaping and building the thin, smooth walls of a pot, firing finished pieces outdoors, and painting detailed designs with a brush made from the yucca plant. Found pieces of broken pottery from earlier Acoma artists and ancestors were also an important resource. The fragments were often ground into the clay to strengthen it and inspired Lewis to develop her own delicate painted patterns.

Lewis grew up with pottery being used for storing food and water or in particular ceremonies. During Lewis’s lifetime, however, Acoma potters began producing smaller vessels to sell to people outside of the village. In 1950, Lewis exhibited her work at the Annual Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial in Gallup, NM, bringing greater attention to her work and the other talented artists of the remote pueblo. Lewis controversially broke with Puebloan tradition and began signing her work the same year, formally identifying herself as an artist.

Other examples of pottery by Lucy Lewis can be found in the collections of the National Museum of Women in the Arts and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

You can also learn more about Acoma Pueblo and the work of other Acoma potters from the Sky City Cultural Center and Haak’u Museum. Look for the work by Carrie Chino Charlie, another Acoma Pueblo artist, in our AR tour. Buffalo artist Cassandra Ott drew this vessel and three others on exhibit. In Ott’s drawing, we see the outlines and patterns of vessels made by (from top to bottom): Carrie Chino Charlie (1925-2012, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico); Artist Once Known (Socorro, New Mexico); Carmelita Dunlap (1925-2000, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico); and Tonita Nampeyo (b. 1934, Hopi-Tewa, Arizona).

WHAT WOULD YOU ASK THE ARTIST, Lucy Lewis?

-How long does it take to make one of your pots?

-What is your favorite part of pottery-making?

-How do you create your painted designs?

ARTIST ONCE KNOWN* (DIQUÍS, CENTRAL AMERICA), GOLD EAGLE PENDANT, A.D. 700-1519. GOLD, 3 X 3.25 INCHES.

This gold bird pendant was made in the region now known as Costa Rica, a country in Central America. One of the older objects in the Cravens Collection, this ancient gold pendant was made by a Diquís or Chiriquí artist sometime between A.D. 700-1519. The terms Diquís and Chiriquí are used by archaeologists and art historians to identify groups of people who lived in this region during that time. Both Diquís and Chiriquí artists created many different animal pendants using gold. These artists and communities were living and working in this region when Europeans arrived in the early 1500s. Because of the distinctive beak and claws characteristic of birds of prey, this and similar bird-shaped pendants were described in Spanish as “águilas,” meaning eagles. Researchers determined that they were worn around a person’s neck. In studying the work of artists from the ancient past, researchers piece together information from a variety of sources. Historic written descriptions, spoken stories passed down through generations, and observations of the objects themselves are all combined to create our current understanding of an artwork.

Look for similar bird pendants and other examples of ancient gold animal pendants from the Chiriquí region at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

WHAT WOULD YOU ASK THE ARTIST?

-Who did you make this pendant for?

-How do you make animal shapes with gold?

-Why did you choose to make an eagle shaped pendant?

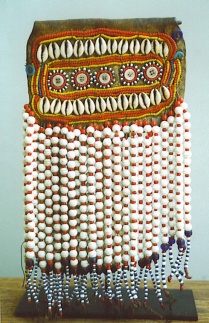

ARTIST ONCE KNOWN* (CAMEROON), BEADED LEATHER, 1930S. COWRIE SHELLS, BUTTONS, BEADS, LEATHER, 14 X 7 INCHES.

This beadwork was made in the 1930s in a place now called Cameroon. Sometimes objects are older than the country that they are from. Cameroon is a country in Africa that declared independence from France in 1960, many years after an artist made this object. While museum staff try their best to learn as much about the objects in their collection as possible, there is always much more to learn. This is the case with this object. One of the ways we can continue our research is to look at other objects from the same place and around the same time period so that we can see how this object is part of a culture. We know a little more about the fertility dolls (discussed below) made by Dowayo artists in Cameroon around the same time period. Watch artist Rachel Shelton talk about the Beaded Leather and drawing it on Vimeo!

WHAT WOULD YOU ASK THE ARTIST?

-Where did you get the beads?

-How long did it take you the string all the beads?

-Can you wear this?

ARTISTS ONCE KNOWN* (DOWAYO, CAMEROON), FERTILITY DOLLS, MID-20TH C. WOOD, BEADS, 5 X 5 X 10 INCHES (TOP); 5 X 5 X 11 INCHES (BOTTOM).

Similarly to the beadwork discussed above, these dolls were made in the mid-20th century in the country now known as Cameroon. They were likely made in the northwestern mountain region by Dowayo artists who specialized in carving and blacksmithing. In Dowayo communities, similar dolls are created for young girls and women. Young girls may be given undecorated wooden dolls to play with and care for, learning about the expectations of motherhood. Decorated dolls, wrapped and draped with varying amounts of beads, shells, and leather, typically belong to women who are hoping to have children. A woman may carry or strap to her back a decorated doll for luck and wishes for a healthy pregnancy.

In addition to being used by Dowayo women and children, Dowayo artists also created similar dolls to sell to tourists and collectors. This matching, decorated pair was likely made to demonstrate the talents of Dowayo artists.

Other examples of similar Dowayo fertility dolls can be found in the collections of the British Museum. Watch Anthropologist Alec Iacobucci talk about his research into these figures on Vimeo!

WHAT WOULD YOU ASK THE ARTIST?

-Does it matter what kind of wood you use to make the dolls?

-How long do you keep the dolls?