Story by ANN WHITCHER-GENTZKE | Illustrations by JOHN JENNINGS

John Jennings centers his life on provocative questions: How can we show the work of underrepresented artists, especially those who do comics? How can we go beyond the racial stereotypes of traditional comic art to show the rich expression of black artists, past and present? And how can we help UB students see that creating art is a possibility for them, to recognize that “art is everywhere” and acquire what Jennings calls “visual literacy?”

Since arriving at UB this past fall, Jennings, associate professor of visual studies, has impressed students and colleagues alike with a sparkling resume of interests and accomplishments. He is at once a nationally recognized cartoonist, designer and graphic novelist. A researcher intent on explaining and “disrupting” black stereotypes in popular media, Jennings disseminates his insights via books, exhibits and lectures that prod people to think about under-recognized voices in American graphic arts. Laced with humor and satire, these are rich expressions of women, gays and others who may have felt themselves invisible in the larger society, but who nonetheless create powerful images of dissent, or moving depictions of their diverse experiences in America.

“I started making comics, or being interested in comics, at an early age,” says Jennings, who grew up in rural Mississippi and counts many artists among his extended family. “I had fallen out from making them for awhile when I was studying graphic design. There are really a lot of talented graphic artists out there, so it’s really difficult to break into the mainstream. I didn’t think I necessarily had the skills to do that properly. So I focused on graphic design as a way to make money and further my scholarship, and myself as an artist.”

After Jennings began teaching at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he’d earned both an MA in art education and MFA in graphic design, he began to reexamine comics, “especially different modes of masculinity and performance. I was also looking at gangster rap, and video games and super hero comics. I became really interested in the racialized body, the hyper-masculine black body.

“So that’s what got me started looking at hip-hop and also comics, too. I began to see that there were a lot of stereotypes in popular serial comics. Even though it’s a hyper-masculine form or genre to begin with, the black male superhero was usually more physical, as far as just showing the body or being depicted as an athlete. You also didn’t see a lot of black male superheroes with telekinesis, or as leaders, or as villainous masterminds for that matter.”

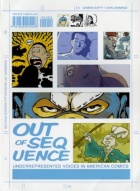

Such thoughts of missed opportunities led Jennings to collaborate with Damian Duffy, editor-in-chief of the Eye Trauma Comix online anthology, in mounting “Out of Sequence,” an exhibition held in 2008-2009 at the University of Illinois’ Krannert Art Museum. An earlier show, “Masters of American Comics,” ran in 2005-2006 at both the Krannert and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. The latter celebrated the work of “15 of the greatest comic artists to ever touch a pen,” Jennings says. Notwithstanding his admiration for the exhibited artists—fabled figures like George Herriman (“Krazy Kat”) and Art Spiegelman (“Maus”)—Jennings thought the show presented “a truncated” view of American comic art.

“Everyone in the show was amazing, but we felt it wasn’t a wide enough view of what comics could be,” Jennings explains. “So we looked at independent comics, we looked at comics about women and by minorities, comics by gay and lesbian artists; also abstract comics, and gallery comics and virtual comics. Because one thing that we realized about the medium is that it persists no matter how you execute it. So we went about turning this show into a kind of narrative and trying to fill in the gaps with content the other exhibit left out.”

The result was “Out of Sequence,” a 2008 book accompanying the show of 65 artists from the early 20th century to the present. The intro is set forth as a string of comic images drawn and colored by Jennings, with Duffy’s writing and lettering in the balloons. The authors continually undermine the notion that comics are always portrayed sequentially, or consist only of lighthearted fare aimed at kids. “We honestly believe that the potential of comics as an art form is limitless,” they state. They also passionately rebut the belief that “only white guys make this art.” The book includes abstract comics like those produced by Andrei Molotiu, “who uses the comic’s idiom and vernacular but with non-objective art,” Jennings explains. The book’s bracing subject matter runs the gamut from bitter social commentary to uproarious humor.

At the same time, Jennings has his fingers on the pulse of hip-hop culture, not with the detachment of an academic researcher studying a phenomenon from afar, but with the passion of an artist who understands hip-hop’s compelling meaning culturally. It’s this panorama of art and cultural studies that Jennings presents in his visual studies classes to students eager to learn more about “Art and the Everyday,” to borrow the title of a freshman course he teaches.

“The Visual Culture of Hip-Hop” is another course Jennings is teaching and one he designed. He characterizes it as a “lecture/seminar/studio” with students from other disciplines joining the primarily visual studies majors.

“Those are the kinds of things I think about constantly—studying race and gender and looking at hip-hop and comics. All are ways to introduce people to the larger conversations about difference and equity.”

—John Jennings

“Mainstream hip-hop is a very deep culture that started in the late ’70s and there are four elements,” Jennings explains for the uninitiated. “These are graffiti, deejaying, MC-ing or rap, and break-dancing or B-boying. Hip-hop is a culture that I think a lot of people don’t know a lot about. They just see the images on television or hear other cultural references.”

Rather, Jennings says, hip-hop is a treasure-trove of both street meanings and scholarly insights. It encompasses everything from activism and aesthetics to identity politics and hip-hop as an industry. Interestingly, “That’s the Joint,” the hip-hop studies reader Jennings chose for the course, was co-edited by UB alumnus Mark Anthony Neal, PhD ’96, now professor of African and African-American Studies at Duke University.

“There’s a really strong hip-hop culture at UB—a B-boy artist on campus is one of the students in my class,” Jennings says. “If you think about deejaying, what they’re really doing is they’re taking a loop or a break and then reproducing it and then remixing it. So we use this idea of sound and re-mixing, which is a very strong part of hip-hop culture, and the idea of the sample. We’re using these ideas to make art—collage, montage, bricolage, re-juxtaposition of images are a main focus of the class.” This spring, Jennings will present the pedagogical model he’s using in the class at conferences on hip-hop studies to be held at NYU in April and Ohio State in May.

Jennings is also a consistent campaigner for visual literacy. Terms like “computer literacy” are household words, but “visual literacy” is almost imperceptible in the public lexicon. “We’re very logocentric as far as the word is concerned,” Jennings maintains, “yet we’re bombarded by images and we’re not taught how to deal with them properly. We should be teaching this early on in school, and I wonder why it’s not, because images are very powerful too. And if you have control of them, then you can control the society. But let me not get too political about that,” he says with a smile.

“Those are the kinds of things I think about constantly—studying race and gender and looking at hip-hop and comics. All are ways to introduce people to the larger conversations about difference and equity.”

“We looked at independent comics, we looked at comics about women and by minorities, comics by gay and lesbian artists; also abstract comics, and gallery comics and virtual comics. Because one thing that we realized about the medium is that it persists no matter how you execute it.”

—John Jennings

Supernatural detective story

John Jennings is working on his second graphic novel, a “supernatural detective story” with the working title “Noir Lock: Hell of a Hangover” and set in prohibition-era Chicago. Supported by a Faculty Research Fellowship from UB’s Humanities Institute, the novel explores aspects of the Great Migration when millions of black southerners moved to the North. “My idea is to look at the informal economy in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago where most African-Americans lived,” says Jennings. “A network of people controlled the numbers racket—in Chicago they called them ‘policy banks.’ My main character is Frank ‘Half-Dead’ Johnson, a conjure man from the South."

Courses taught

Courses John Jennings is teaching in Department of Visual Studies:

Support UB Humanities Institute

Support UB Visual Studies

Apply to UB Visual Studies

Show to explore ‘Black Kirby’

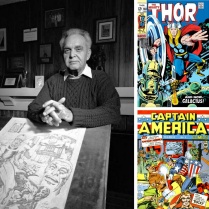

As a child, John Jennings recalls his mother bringing home a comic book, “The Mighty Thor,” created by Jack Kirby (1917-1994) and loving it. “I began drawing and never stopped,” he says. Jennings and illustrator Stacey “BlackStar” Robinson will pay homage to Kirby in an exhibit opening in September at Jackson State University. The show will explore parallels between the experiences of Jewish-American artists like Kirby and African-American stories in comic literature and popular narratives.

John Jennings book credits:

Black Comix

What “black,” “art” and “culture” mean to a group of African-American artists.

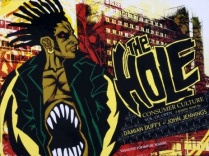

The Hole: Consumer Culture

Graphic novel is science fiction/horror story about buying and selling of race.

Out of Sequence

Underrepresented voices showcase their imaginative comic art.